I got my first typewriter at age 7, thanks to Santa’s wise and forward-thinking parental elves. Five decades later, I still type every day. The technology is MacBook Pro laptop instead of finger-spraining manual Underwood, but my goal is the same:

Write like my hair’s on fire.

Which is why I have less of it now than at age 7. (That’s my story and I’m sticking with it, thank you.) But enough about hair; you’re here for a glimpse of The Author’s Life, both professional and personal. I appreciate your interest, so I contacted the very best interviewer who’d work for free—Me—and asked him to do the honors. Me was agreeable and dropped by Casa Gericke with a bottle of Ardbeg (note to new writers: yes, Shane can be bought for Scotch, but only the good stuff, not the five-buck-chuck) and a deep-dish Chicago pizza. We went into the rec room, unpacked the food and booze, and before I could say “cheers” or even “chin-chin,” he hit me with the most tedious interview question next to, “If you were a tree, what tree would you be . . .”

Q. So, Shane, boxers or briefs?

A. “Sergeant Fury” doesn’t like close quarters. So, commando.

Q. <sighs> I’m gonna regret taking this gig, aren’t I?

A. Yeah. But that’s why we have the Scotch.

Q. <brightens> <takes noisy, three-gulp swig> <grimaces from alcohol-fueled nasal fire> <scoops out battleship-sized triangles of thick and delicious sausage pizza from container redolent of hot, damp cardboard>

A. Lou Malnati’s deep-dish. Excellent choice. You know from Chicago pizza, my friend.

Q. Back atcha. But what I really want to know is, How come it’s spelled “Gericke” with a G, but pronounced “YER-kee” with a Y. Were you dropped on your head at birth?

A. Yes, but that’s not the reason. When the seven Guericke brothers (note the additional U in the surname, which provided the “YER” sound in the pronunciation) emigrated from Germany in the 1800s, a bureaucrat chopped out the “U” to make the name, um, “more American.” All that really did was give us Gericke descendants a headache trying to explain YER vs. GRR pronunciation.

Q. Are there any famous Gerickes? I mean, besides you?

A. Sure. Uncle Otto.

Q. Er, um, ah, sure, but refresh my memory . . .

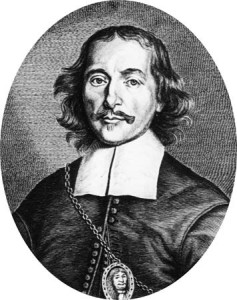

A. That would be Otto von Guericke (portrait, left), aristocrat, inventor, and mayor of medieval Magdeburg, Prussia (now Germany) in the mid-1600s. Note the “U” in Uncle Otto’s “Guericke,” which makes YER conflict with GRR which makes me—

Q. PURR? <grin> What about “Shane?” Are you named after someone?

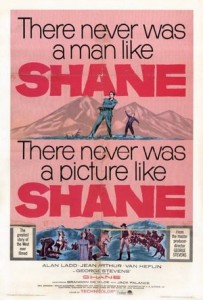

A. Not someone, but something: the cowboy movie from 1950, “Shane.” The little blond kid chasing after gunslinger Alan Ladd hollering, “Shane! Come back, Shane!” Remember that? My folks did, and when I popped out in 1956, they handed it to me. Which I appreciate, despite the phonetic challenges: “Shane Gericke” is a cool name for a writer. It’s exotic enough to stand out, and gender-less enough to let readers assume what they want. Best of all, my books sit next to literary phenom Tess Gerritsen’s on store shelves. When fans reach for her book and grab mine by accident—yes, it has happened, and more than once—I ring up a sale. Thanks, Tess!

Q. Tess says you’re welcome. I hear you got hooked on writing at age 7. True?

A. True, and for that you can credit Mrs. Feely. I was in second grade at Ann Rutledge Grade School in the tiny town of Lincoln Estates, forty miles south of Chicago. One snowy morning I was practicing Parker Penmanship on one of those lined gray tablets with the wood slivers embedded in the paper. (I have no idea why I remember these weird little details. I just do.) My teacher, Mrs. Francis Feely, hair of snow and eyes of plutonium (she didn’t miss much), walked into the classroom with a stack of mimeographs—

Q. Mimeographs? What the heck is a mimeographs? Some kinda French mime, right? Knobby knees and a pastel beret? Geez, I hate those glass rooms they build . . .

A. Chill, dawg. Mimeograph machines (also called “dittos”) were the precursor to Xeroxes. Teachers typed a handout onto a stencil master. They hooked that to the ditto machine and cranked the handle. Voila, copies popped out the other end. It was a “wet” technology, not dry like the later Xeroxes, so the copies were damp from the blue ammonia “toner.” You could get high breathing that stuff. In fact, there was a scene in the movie “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” where an entire classroom of kids sniffed a mimeo’d test in unison and—

Q. Uh, never mind. What was this mimeo’d doohickey she handed out?

A. Mrs. Feely called it a newspaper. There were “news” stories about events and people at the school. Each story was topped by the name of an eighth-grader.

Q. They call that a byline, right?

A. As in, “By David Robinson” or “By Drake Tungsten,” right. The stories were written by the eighth-graders and distributed to the entire school, which didn’t take long; we had only 130 kids in grades one through eight. (No kindergarten back then; to this day I am deficient in napping and rounded scissors.) Lincoln Estates was an unincorporated hamlet of about 300, just two miles down the Lincoln Highway from Frankfort, our local “teeming metropolis” of 2,000. (Chicago, 40 miles north, was a magical trip to the Land of Oz, except the yellow brick road was Harlem Avenue.) Classic small-town America, Lincoln Estates was: one gas station, two churches, three taverns, and scores of all-American families who called it Home.

Q. So you liked this smelly purple newspaper?

A. I was enchanted. This was news! It was happening right now! More important, everybody admired newspaper writers! I asked Mrs. Feely if I could have a byline. Not missing the opportunity to slip a spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down—teachers are wily that way—she said, “If you learn proper English, reading, spelling, and punctuation, yes, then you could write for a newspaper.” Though given what I see on the Internet these days, her theory has changed, and not for the better.

Q. That’s when you knew you wanted to be a writer.

A. Not just a writer, but a newspaperman! Seeing those bylines on that smelly mimeo flipped a switch inside me, and I never looked back. Sadly, by the time I got to eighth grade, the school board had killed the newspaper—budget cuts. But I got to write for the high school paper, the Lincoln-Way Squire (the school mascot was the Knights, we were the Squire, get it?) and became editor in chief. Fun fact: The Squire’s music reviewer was Karla DeVito, who went on to become the female lead singer with rock star Meat Loaf. “Paradise by the Dashboard Light.”

Q. Was that your first big break?

A. Yes. But there were more. Like most Americans, we writers like to pretend we became a success entirely on our own, pulling ourselves up by our verb-encrusted bootstraps whilst crouched over a stone tablet carving Trvth. The reality is we’d never become published without the help of teachers like Francis Feely and editors like Ed Czerwinski, who ran my hometown weekly, The Herald. He was looking for someone to cover high school sports, and asked the principal at Lincoln-Way if anyone was interested. I was, and I met Ed in the newspaper’s office: a battered warren of rooms attached to the back of a restaurant.

Q. How’d the meeting go?

A. Swell. This was the big-time for a small-town kid—the office smelled like a paper mill from all the yellowed newspapers piled about. It had battered telephones, typewriters, carbon paper, and grease pencils, the essential tools of the trade back in the day. We used the darkroom in the back to develop the black-and-white film we shot (Tri-X Pan, for those who remember the glory that was Kodak). We talked awhile, and then he treated me to lunch. I was thrilled. Every newspaper should come with its own restaurant.

Q. You took the job?

A. In a heartbeat. Ed asked me to cover Lincoln-Way sports: football, basketball, and baseball every week, with stories on “minor” sports like wrestling and gymnastics as time permitted. I’d cover every ballgame, home and away, write features, and take all the photographs. For this he offered the princely sum of $30 a month. I couldn’t believe I was getting paid to write about sports, and thought this was so much money I’d never need any more in my life.

Q. I trust you came to your senses about moolah?

A. Mother Gericke raised no stupid children. After a year and a half of working for Ed, I went to college to pursue a journalism degree. While attending classes, I worked as a paid reporter and editor at the Northern Star, the student newspaper at Northern Illinois University. I spent four happy years in that job. I met my wife, Jerrle, in the newsroom. (I wrote news, she covered sports. A match made in heaven.) I wrote a feature about a scrawny local nudist who decided to run for President, and it got picked up by a Chicago magazine. A polemic I wrote about our disgraced college president was judged the nation’s best college newspaper editorial in 1978 by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation. I flew to San Francisco to pick up my award. It was the first time I’d ever been on an airplane.

Q. If you were a tree, what tree would you be?

A. Bite me.

Q. Guess that makes you a softwood. <snickers> When did you get your first full-time newspaper job?

A. Right after I graduated college in 1978. I was hired by the Daily Dispatch in Moline, Illinois, one of the fabled Quad-Cities of Moline, Rock Island, Davenport and Bettendorf. It was a demanding job, and my boss, Gerald Taylor, liked how I was willing to try anything, so he let me go to town. I learned a ton about story editing, page layout, working under deadline pressure, and producing high-quality daily newspapers. I worked there three years, then took a similar job with the Joliet Herald-News, a paper with a bigger circulation and much closer to where I’d grown up south of Chicago. I worked the midnight shift for a year and a half, and then got the phone call for my dream job.

Q. The show? The varsity? The big dance?

A. Yes, yes, and yes—I was gonna work for the fabled Chicago Sun-Times. I’d grown up reading that newspaper—my folks had it delivered to the house—and in 1982, the year I started, it was one of the nation’s leading newspapers. Mike Royko was a columnist. Ditto Ann Landers, Roger Simon, and Roger Ebert, the Pulitzer Prize-winning movie critic. The chief copy editor had kept my resume—I applied for a job during my senior year at NIU—and he figured what the hell, give the kid a chance. I was hired as an editor in the business section, which was expanding to take on the bigger Chicago Tribune, which was across from the Sun-Times Building in downtown Chicago. The Sun-Times Building was demolished and replaced by Trump Tower Chicago.

Q. Is the Billy Goat Tavern nearby?

A. The famous Saturday Night Live “cheeseborger, cheeseborger, no fries, cheeps” skit was based on that newspaperman bar, which was literally yards from the basement door of the Sun-Times. My job interview was held at the Billy Goat. The chief copy editor liked to get candidates drunk to see if they could hold their own under the influence.

Q. Or perhaps the chief copy editor liked drinking on company time?

A. Ummm, perhaps. After our second pitcher of dark beer—two guys, two pitchers, what could go wrong?—he decided he liked my style and offered me the job. My hangover the next day was Brobdingnagian—that’s a ten-dollar word for “really big”—but so worth it. One of my most cherished writer-guy memories.

Q. How long did you work there?

A. Started in 1982, left in 1999. By then, I had worked in newspapers for a couple decades, and was also chairman of the Chicago Newspaper Guild, the reporters’ union at The Bright One.

Q. The, um, “Bright One?”

A. What the paper called itself in radio ad campaigns: “Wake up, wake, up, wake up, wake up, wake up to The Bright One, the Chicago Sun-Times!” (Don’t blame me; I didn’t write the jingle.) Anyway, I loved being an ink-stained wretch, but the thriller-novel itch had gotten too big to not scratch, and the shiny new millennium seemed a good time to do it.

Q. What is a thriller novel? How does it differ from a mystery novel?

A. I define a thriller as a mystery on crack. In other words, a thriller is a story built for speed. It’s designed to grab readers by the eyeballs and hurl them down the train tracks to the collapsed bridge over the waterfall as a hurricane bears down on the nuclear power plant that’s under siege from terrorists firing Ebola-coated bullets from machine guns.

Q. And a leggy young scientist with doe eyes and fearless spirit (and Jeep that needs a good washing) who’s the only character brilliant enough to Save Our Planet from the Hellbeast of Extinction?

A. I was trying not to be sexist. But now that you mention it, well, as long as she admires hunk-a-riffic writers with pewter hair . . .

Q. “Pewter?” You’re grayer than winter in Scotland. Grayer than perch gone bad. Grayer than the fate of Old Yeller–

A. Said the pot to the kettle.

Q. Um, well, touché. So, you’ve always wanted to write thrillers novels?

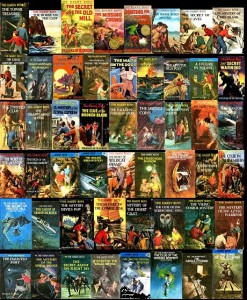

A. When I was a kid, my maternal grandmother took the train from Chicago to visit. (The Illinois Central electric line, for those of you familiar with Chicago transportation.) Every visit, “Nana” brought each of her grandkids—I have two sisters, Marianne and Diana—a book to read. (Thank you, employee discount at Marshall Field’s!) Marianne received “Nancy Drew, Girl Detective.” Diana got “The Bobbsey Twins.” I got “The Hardy Boys,” the long-running series starring teenage brothers Frank and Joe Hardy, who solved crimes and thwarted criminals alongside their dad, “world-famous detective Fenton Hardy.” My own father was a police sergeant, so reading these crime capers was kinda-sorta like I was out on patrol with Dad, catching no-good-niks. (In college, I got to ride along with him on the midnight shift, drinking over-boiled cop coffee and listening to war stories. Swear to God, cops and firefighters tell the best stories. Another fond memory.) I loved those detective books, read them under the covers with a flashlight late at night, which my parents pretended not to notice because I was reading, an activity of which they heartily approved. The Hardy Boys made me think that someday, maybe, I could write a crime novel. Two decades in newspapering seemed perfect training for that job, so, brimming with Everest-sized overconfidence, I left a perfectly sensible newspaper job for the vagaries of book publishing.

Q. But you were an overnight success, right?

A. Wrong, mimeo breath. My first two manuscripts didn’t go anywhere—I queried a hundred literary agents and publishers, and not one of them took it. They admired the writing but declared the subject impossible to publish—religious terrorists strike the United States—so they’d take a pass. (Remember, this was pre-9/11.) Looking at the manuscripts now, I can see the writing was uneven—crazy good in some spots, sputum in others. But the emotions, the passion; those things pulsated off the pages like heat rays. The story was there, but I simply didn’t know how to tell it correctly. Long-form writing is an art unto itself, and must be learned through endless hours of writing, cussing, and rewriting. In journalism, a long story is 1,000 words. In fiction, you’re talking 90,000 to 120,000. Story management is entirely different, and I didn’t know that. But I kept at it and learned.

Q. Leading to your first published novel in 2006.

A. Yes, Blown Away. After my religious terrorism manuscripts went the way of the passenger pigeon, I decided to write a nice little crime story starring a female cop who fights a serial killer—Emily Thompson, rookie police officer in Naperville, Illinois, the Chicago suburb where I live now and where my crime trilogy is based. I reminded myself to keep it simple and exciting, skip the fancy allusions and rhetorical flourishes. I finished it and found a literary agent to make the rounds on my behalf. Kensington Publishing bought the rights. Remember I said I’d written Blown Away as a nice little stand-alone cop thriller? Well, Executive Editor Michaela Hamilton had grander plans, and asked if this was a series debut. I lied like a rug and said yes. (Only a dope turns down a multi-book deal, right?) I had almost no time to concoct a plot for the second book, but I managed, and Cut to the Bone was the result. Torn Apart became the third of my bestselling crime trilogy. So yes, I was an overnight success—only twenty-five years of practice, two unsold manuscripts, and a hundred rejections. Easy!

Q. Can I buy your first three books along with The Fury?

A. Yes, and I’d be right pleased if you did. Find them on Amazon.

Q. Did you expect to make millions on your first manuscript?

A. To be painfully honest, yes. I was counting my chickens not only before they were hatched, but before the rooster got that certain gleam in his eye for Henny Penny. When I wrote Crusade, my first manuscript, I was planning the New York Times-bestseller party before I mailed the first box to the first agent. Two weeks later the letter appeared in my mailbox: We’re sorry to inform you . . . . Ditto on the followups: Rejected! Rejected! Rejected! You . . . are . . . rejected!!! More than a hundred rejections.

When a nail is tired of being hammered, it either disappears into a hole or it bends. So I abandoned religious terrorism for a simple cops-and-robbers tale. By the time I finished writing it, my expectations for success were considerably, uh, lessened. So honestly, I wasn’t expecting anything extraordinary—sell a few thousand copies, earn a few reviews, and build on that.

Blown Away came out May 6, 2006. On May 23, my editor called to say congratulations, you’re a national bestseller. I’d turned 50 that very day, and I was speechless. As a baby novelist, you honestly have no clue whether your own mother will like your work (for the record, yes, she did), let alone millions of strangers with choices on how to spend their entertainment dollar. But they did, and Blown Away went on to win Mystery of the Year honors from RT Book Reviews along with a truckload of stellar reviews. Foreign publishers snapped up translation rights: Germany, China, Slovakia, and Turkey. Cut to the Bone appeared the following year, and after that, Torn Apart, which was shortlisted for the Thriller Award for Best Novel (a very big deal) and named a Book of the Year by Suspense Magazine, all of which helped ease my lingering embarrassment at my overweening early overconfidence.

Q. So, the trilogy was shipped, sold, and read. What came next? Emily Thompson No. 4?

A. Something even cooler: my first global thriller!

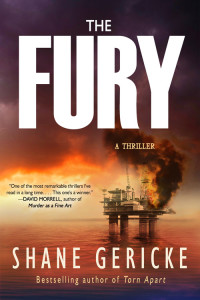

Tantor Media released The Fury on September 4, 2016. The characters arc-welded themselves to my brain cells, meaning you’ll like hanging out with them, too. The plot’s full of jet fuel, and the cover glows so intensely your retinas will burn. I’d love to show you, but you’ve got that interview with the Kardashians . . . um, really? You want to see it anyway? I’d hate to make you miss your time slot, Kardashians are so hard to pin down for interviews . . . well, all right, since you insist, but if Kim abandons you for a cable TV interview, don’t blame me.

Q. <sees book jacket. widens eyes.> Woof, dawg! That IS an awesome cover! What’s the book about?

A. Terrorism.

Q. Can you be more specific?

A. Global.

Q. <drums fingers impatiently on sodden pizza box>

A. All right, all right: If a grief-blinded cop fails to hunt down the man who murdered her husband, millions will die from a nerve-gas attack on the United States. Including you.

Q. Me? Eeeek!

A. What I said when I wrote it. My hero is Superstition “Sue” Davis. She has a ferocious uppercut and a million-dollar smile. The drama is set in Chicago, where Superstition works as a Chicago Police undercover officer, and the Arizona-Mexico border, where unspeakable cartel brutality takes place. The story contains flashbacks to real events in World War II and the Cold War, which I use to show the development of the doomsday weapon central to my story. Which weapon, VX nerve gas, is, by the way, for real. A drop the size of Abe Lincoln’s eyeball on a copper penny will kill a full-grown human. Every bomb contains millions of drops. Do the math.

Q. Doomsday bombs? Gimlet-eyed terrorists? Narcotics wars with Mexico? Cartel tunnels dug under Arizona? Adolf Hitler, nerve gas, Japanese human experimentation labs, and a big bad babe named Superstition? Wow! There’s a whole lotta meat on THAT slab of ribs!

A. It’s my most ambitious work yet. <scarfs another triangle of pizza> This book took years to research and write—there are a lot of moving parts, with many of the scenes based on or suggested by actual events. (See Real Fury for the scoop of what my research found.) I lived in Chicagoland most of my life, and moved to Arizona a couple years ago, so I’m intimate with both worlds. I’ve been to Nogales (both Sonora and Arizona), and I flew to Germany to explore the Eagle’s Nest mountain complex in the Bavarian mountains, where Adolf Hitler planned many of his atrocities. But the finished book will wow you. How do I know? Because it wowed me. Which is exceptionally difficult to do, because I’m such a harsh critic of my own work. I was tickled pink to see this story published.

Q. “Tickled?” Not very macho for a thriller writer . . .

A. Tickle this, mi hombre.

Q. Put that thing away, you’ll shoot your eye out! <accepts applause for sly homage to A Christmas Story> All right, switching gears: even though book characters are faker than an alderman’s smile, do they seem somehow real to you? Does it feel like you could invite them for dinner and they would show up?

A. Of course they seem real. I have conversations with them all the time, just like with flesh-and-blood friends. The character conversations are strictly in my head, of course. If we actually talked aloud, the friendly folks in the white coats would come a-callin’.

Q. Does everyone in Chicago say, “Da Bears!” like those Superfan guys on TV?

A. Yes.

Q. Awesome, dude!

A. We don’t say “awesome, dude.” Ditka don’t surf.

Q. Sorry, just back from L.A. All right, translate this into Chicago for me: “Say, good fellow! Let us gather our chums who mill at yonder dockside conversing with the mayor. We shall partake in fine dining, and then attend a sporting event, where the battle will be fierce but fair and the best team shall prevail.”

A. <clears throat> “Yo, Skeezix! Grab dem guys standin’ by Da Mare—yeah, yeah, over dere, by dat dinghy, ya blind—an make it snappy. We’ll stop by the Jewel’s for hot dawgs and sammiches, den go watch Da Bears cream Da Packers, who are suckwads.”

Q. “Skeezix”?

A. Just seeing if you remember your Chicago comics heritage.

Q. Haw! I remember Gasoline Alley now! So, you gonna wash down your “hot dawgs” and “sammiches” with Pabst Blue Ribbon—

A. PBR? Seriously? What did I ever do to you?

Q. Point taken. <urp> Is Superstition Davis, the hard-charging hero of The Fury, a real-life Chicago vice cop but you changed her identity to protect the innocent?

A. You mean like on Dragnet? No. Sue isn’t real. She’s a figment of my overcaffeinated brain. Just like Jimmy Garcia, Robert Hanrahan, Jerome Jerome, Deb Williams, Emily Thompson, Marty Benedetti, Annie Bates, Hercules Branch, the Zodiac killers, the Executioner, the magical deer, and all the other characters in my four books: fictional. Basing characters on actual human beings limits what I can do with them in the books. So I make them up. (Speaking of Dragnet, check out this hilarious sendup of Sergeant Joe Friday: The Copper Clapper Caper.)

Q. How do you toast yourself when you’re done making stuff up?

A. If you’re referring to alcohol, and I think you are, what makes you think I imbibe?

Q. You’re a writer.

A. Good point. My favorite Scotch is Ardbeg, an uber-smoky single-malt that makes my ears buzz like happy little honeybees. It goes great with deep-dish. Course, everything goes great with deep-dish, doesn’t it?

Q. I’ll say. Any movie possibilities for your books?

A. Flurries of interest, but nothing solid. That’s Hollywood—no movement for years, then bam comes an eye-popping offer. I’d like that. I could get one of those Kangol hats and wear it backwards, like Tarantino! And, the South of France is lovely this time of year, I hear. Of course, I’d settle for the South of Poughkeepsie, I’m easy . . .

Q. Do you enjoy the research required for your books?

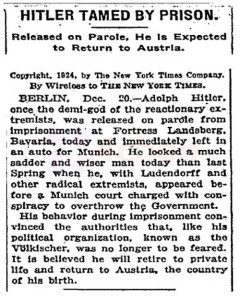

A. Yup. I love finding out stuff I didn’t know before. Like this oopsie from the New York Times, which proclaimed that Hitler was a weenie and no longer to be taken seriously. Check out Real Fury elsewhere on this website for details of all my research.

Q. Guess someone forgot to tell Hitler! What do you like to do when you’re not writing?

A. Hike the glorious Sonoran Desert. Read. Travel. Shoot. I used to do all that with my honey, who coincidentally was my wife of four decades, proving that yes, one CAN live happily ever after, but sadly, she died in 2015 of metastatic breast cancer. MBC is more evil than any cartel enforcer, I’ll tell you.

Q. Ah, geez, cancer sucks. I’m sorry for your loss, man.

A. Thanks. Me, too. She was a helluva woman and my writing muse. But her memory will love on through my books, each of which is dedicated to her.

Q. Back up a minute. What do you mean by “shoot?”

A. I’ve owned, operated, and studied firearms, primarily handguns, most of my life. Good thing, too: most thrillers contain guns and gunfights in some shape and fashion. The smart author gets those details right.

Q. Details like what?

A. “Dick Steele whipped out his Glock, snicked off the safety, and opened fire.” Glocks don’t have manual safeties, and to proclaim they do tells readers familiar with such that you’re pulling it out of your caboose, which shreds your credibility. Or, “Harli Danger screwed the silencer onto her revolver.” Silencers don’t work on revolvers, only on semiautomatics. I take the same approach to real-life landmarks, cities, nations, street intersections, wildlife inhabiting a particular place (i.e., there aren’t any dung beetles in Chicago except maybe our politicians), details of historical events, and the like: Accuracy counts. People who know something about those subjects get crabby when you screw it up, so I try not to screw it up. Google is my copilot.

Q. What’s your personal favorite gun?

A. Springfield Armory’s XDM-9, a tough little pistol that holds eighteen rounds of nine-millimeter ammunition. It’s strong, lightweight, fits my hand perfectly, points naturally, and shoots without a single hiccup. I customized mine with high-visibility sights to accommodate my aging eyes.

Q. So naturally all your characters carry XDM’s with high-visibility sights for aging eyes?

A. Not a chance. To write convincing fiction, I have to live in their worlds, not mine. So I equip my characters with the gear they’d use if they were real: Glock pistols and AR-15 rifles for American law enforcement. AK-47 rifles and RPGs—rocket propelled grenades—for the narcoterrorists. Characters need to use what’s right for them in any given situation, not what’s right for me personally. Separate worlds.

Q. Who were your early writing influences?

A. Newspaper reporters. I spent a couple of decades in the business, including the Chicago Sun-Times, one of the nation’s great newspapers back when being a newshawk meant something more than covering the Kardashians. So, I revere serious journalists, because they are gods—nobody else keeps an eye on the government and corporate leaders who affect our daily lives.

In fiction, my earliest influence was “Franklin W. Dixon,” who wrote the Hardy Boys series beloved by millions of boys and girls worldwide. “Dixon” was the pseudonym for the posse of freelance authors who wrote the books for the series syndicator.

After that came Mickey Spillane and his Mike Hammer; Robert B. Parker and his Spenser; John Sandford and his Lucas Davenport and Virgil Flowers; and Frederick Forsythe for Day of the Jackal, a book I read so many times the pages literally fell out. I tried to love Robert Ludlum, but his plots were so twisty-turny I couldn’t keep track. Gayle Lynds kept up his tradition after he died, and she was far easier to readd. All those cool adventure stories made me dream I could be a thriller novelist someday.

Q. And now you are.

A. Yes, thanks to the wonderful readers who buy my books. Without them, I’d have to work at, um, THIS PLACE, which would, I have to admit, really, really, really, really suck. Really.

Q. Who are your favorite authors now?

A. My Top Three are James Lee Burke and his Robicheaux series; John Sandford and his Prey series; and Lee and Andrew Child and their Jack Reacher series. Burke has no peer in descriptive language; I can smell, taste, and hear the swamps of South Louisiana where his main character, New Iberia Sheriff’s Deputy Dave Robicheaux, chases bad guys and, occasionally, the ghosts of the Confederacy. Sandford features two dynamite lead characters–Lucas Davenport and Virgil Flowers–a move-it-along writing style, and eye for telling details, and dark cop humor) so compelling that if he wrote auto repair manuals, I’d read them. As for Jack Reacher and his creators, what can I say but, Wow.

Q. Any other authors you admire?

A. Oh God yes. Dozens. Scores. Hundreds. Fiction and nonfiction. Even the folks who write the copy for the back of cereal boxes. But to list one I’d have to list them all and there’s not enough digital ink on the Internet.

Q. I hear you were an Eagle Scout.

A. Still got the medal in my desk drawer. Sadly, I do not fit in my little khaki uniform any longer, for I am no longer little. But Mom sewed my patches and merit badges on an old U.S. Army blanket (Dad served as a combat engineer in Korea. He brought back a blanket. Go figure) and gave it to me when I got married. So I’ve got that going for me, which is nice.

Q. <turns wistful> I only made Tenderfoot in Scouts. Whenever I whittled a stick I cut my hand, so they made me join Camp Fire Girls. <pout>

A. I’m sorry. You can have my merit badge blanket if you want. Use it as a napkin for your deep dish.

Q. Really? Thanks! <tucks blanket around thick, working-class neck, immediately slops tomato sauce on Beekeeping merit badge> Do you actually read thriller novels, or do you just write them?

A. I devour thrillers with even more enthusiasm than pizzas. Thriller novels are the highest form of literature. Quit rolling your eyes; thrillers tell hard truths about life, they keep your attention till the very last word, they’re chock-a-brim with a deep understanding of the human spirit, both pure and evil, and the writing is crisp, clear, and exciting. That’s the very definition of “literature.” Proust, Faulkner, Joyce and the other literary “gods” could have taken lessons from David Morrell, Steve Berry, and Laura Lippman.

Q. James Effing Joyce. Sweet Jesus, I hated Ulysses.

A. Everyone hates Ulysses. It’s as reader-friendly as a porcupine dipped in anthrax. And don’t get me started on Finnegan’s Wake, the most portentous slab of “writing” I have ever tried to read. “Sod’s brood, be me fear! Sanglorians, save! Arms apeal with larms, appalling. Killykillkilly: a toll, a toll. What chance cuddleys, what cashels aired and ventilated! What bidimetoloves sinduced by what tegotetabsolvers! What true feeling for their’s hayair with what strawng voice of false jiccup! O here here how hoth sprowled met the duskt the father of fornicationists but, (O my shining stars and body!) how hath fanespanned most high heaven the skysign of soft advertisement! But was iz? Iseut? Ere were sewers?” Really? If I’d handed that to my publishers, my next “book” would be the employee’s manual at McDonald’s on how to flip a burger. But this is considered Literature. Sigh. Give me two liters of James Lee Burke, stat. Stirred, not shaken.

Q. True dat. Hey, thanks for asking me to conduct this interview, Shane. It turned out to be fun, and you paid for the eats without claiming you lost your wallet. You’re not nearly as big a weenie as everyone says.

A. Thanks. I think.